The following passages are excerpted from students’ responses to Susan Sontag’s controversial essay “The Decay of Cinema,” New York Times, February 25,1996. Students chose a range of other essays by other critics in order to contrast their attitudes towards cinephilia, the theatrical experience, and digital technologies with Sontag’s. These essays include: Manohla Dargis’ “The 21st Century Cinephile,” New York Times, November 14, 2004; Jonathan Rosenbaum’s “DVDs: A New Form of Collective Cinephilia,” Cineaste,Vol.XXXV No.3 2010 and Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010); Tsai Ming-liang, “On the Uses and Misuses of Cinema, http://www.sensesofcinema.com, 2011; and Christian Keathley, Cinephilia & History or The Wind in the Trees (Bloomington: Indiana, 2006). Below is a selection of terrific responses. Enjoy.

The following passages are excerpted from students’ responses to Susan Sontag’s controversial essay “The Decay of Cinema,” New York Times, February 25,1996. Students chose a range of other essays by other critics in order to contrast their attitudes towards cinephilia, the theatrical experience, and digital technologies with Sontag’s. These essays include: Manohla Dargis’ “The 21st Century Cinephile,” New York Times, November 14, 2004; Jonathan Rosenbaum’s “DVDs: A New Form of Collective Cinephilia,” Cineaste,Vol.XXXV No.3 2010 and Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010); Tsai Ming-liang, “On the Uses and Misuses of Cinema, http://www.sensesofcinema.com, 2011; and Christian Keathley, Cinephilia & History or The Wind in the Trees (Bloomington: Indiana, 2006). Below is a selection of terrific responses. Enjoy.

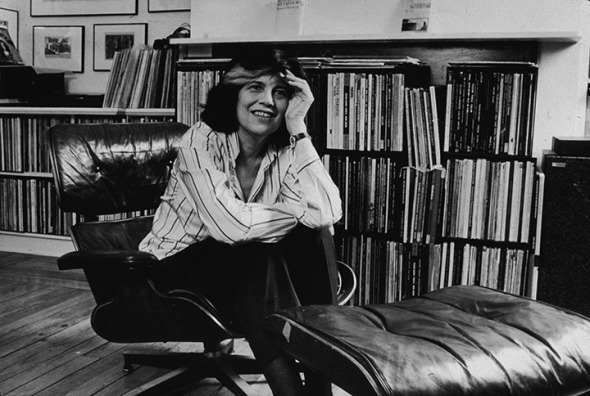

— Prof. Rich

Susan Sontag’s article on “The Decay of Cinema” is, perhaps, a little alarmist, and certainly romanticizes the past more than is wise. But despite the fact that Sontag ignores any films that were less than masterpieces in the earlier days of cinema, and despite her obvious distaste for current mainstream films (which, in my opinion, are not all pure evil schemes with no purpose other than to make money…I’ve seen one or two blockbusters that I enjoyed), Sontag did make some interesting points, particularly in her paragraph on being “kidnapped” by a movie.

— Zoe Toffaleti

True, there is certain magic to sitting in a dark room with strangers and watching a world unfold for us to lose ourselves within, but the world has changed. I feel as though Sontag wants to return to a time when cinema lovers were an elite group of geniuses and because there are no select geniuses filling those shoes, she concludes that the practice of loving and examining film has died. On the contrary, much like a system overhaul from tyranny to socialism, the love of cinema has been dispersed amongst the people far and wide. Endless blogs discuss films: not just Hollywood-canon films, but films from all over the world, brought to you by the internet. As Jonathan Rosenbaum points out, “it surely matters that various films that were once literally or virtually impossible to see are now visible.”

— Connie Peterson

Manohla Dargis recognizes a shift of cinephilia, rather than the death of such, in her article, “The 21st Century Cinephile.” She notes Susan Sontag’s fear of what the decrease in theater audiences means for cinephilia. However, she sees the cause (an increase in people watching movies at home) as an advantage. Seeing movies at home allows the public to see a larger variety of movies. Dargis points out that DVD collectors taking pride in ownership of distributed movies drive a new style of cinephilia. While recognizing issues with streaming movies on the internet, Dargis connects the public’s development of a vast knowledge of movies to the rise in film festival popularity. There is no denying that a change in cinephilia is present. However, when considering Dargis’ view of festivals as a necessary distribution network, the change calls for less mourning and more recognition of varied film knowledge obtained by the public. There is still a love of cinema: this is more evolution than death.

— Laura Hartung

Sontag’s many erroneous arguments – like her assertion that the “conditions of paying attention in a domestic space are radically disrespectful of film” – are … a complete slap-in-the-face to whatever community of cinephiles does indeed exist. I watched Stella Dallas (Vidor, 1937) on a 13” MacBook screen last week without any distractions on the part of loudmouth roommates, text messages and doorbells because I was enamored of Barbara Stanwyck and would enjoy that film on any given apparatus. Cinephiles should object to Sontag’s misuse of apparatus theory (which is already so well delineated by such theoreticians as Christian Metz, Laura Mulvey, Jacques Lacan, Jean-Louis Baudry, etc.) because her discussion is so narrow-minded and joyless; she may as well be writing for Cahiers circa 1950 (sic). To assert that one can only enjoy films in a “darkened theater” not only elides the very sad reality of diminishing, small-scale and/or independent movie theaters, it also makes the offensively bourgeois case that cinephiles should exist in urban centers, near theater outlets to spend at least $70 per week watching features.

— Will Felker

While I believe Sontag’s argument about new technologies forcing out the experience of going to the cinema holds some weight, I think she fails to acknowledge the benefits of technology. Because of the advent of home video, and ultimately DVD and Blu-Ray, more films are widely available than ever before. More importantly, the accessibility of DVD has allowed film culture to move outside of the dominant cultural centers. While seeing a great film in a packed theater may constitute an optimal viewing situation (and this claim can easily be contested), this is an experience that can only be had in a major cultural center. Theaters willing to play daring or original films are generally only found in the big cities. The possibility of home viewing fixes this problem, and allows for film culture to spread beyond the cultural elite.

— Quinn Gancedo

Jonathan Rosenbaum calls DVD the “new form of collective cinephilia.” Rosenbaum has a much more positive outlook on cinema and cinephilia than Sontag. He argues that cinephilia is not dead: it has just changed its nature in conjuncture with the times. Whereas Sontag pushes for the viewing of films solely in the darkness of a theater, Rosenbaum is willing to utilize the DVD. Essentially, he states that sometimes, DVDs offer better picture quality than some prints of films and the viewing of a film in “optimal form” will change from picture to picture. “So we need to step away from absolutist positions about the future and make use of the best possible choices available to us in the present.” Willingness to accept the DVD offers a possibility for cinema to become more widely accessible and admired. Instead of condemning the times we live in, Rosenbaum argues that we need to adapt.

Both Rosenbaum and Sontag realize that film as an art form is changing. Whereas Sontag sees this change as bleak and negative, Rosenbaum sees the change as not bad, just different. He understands the times we live in and knows that even if masterpieces are fewer in number than they were in the early days of cinema, there is, with the help of DVD and internet technology, still a place and way for cinephiles to watch, discuss, debate, and truly love the cinema.

— Gabrielle Kovacich

Sontag’s discussion of the loss of a certain kind of love for the cinema is one that resonates deeply with me because I share her sentiment that this moment in history is one worth critically addressing. Although her tone is characteristically pessimistic and fatalist about this moment, suggesting that we are powerless to the forces that have engendered it, I hope to find ways in which we can make it out of this one alive.

Tsai Ming-liang discusses the end of cinema in similar ways in his article, “On the Uses and Misuses of Cinema.” He poses the questions (and I paraphrase), “Why should we continue to make movies for economic gain if this was not the purpose for which they were intended? What happened to the original intent of creating movies for poetic expression? Why have films seized to express us as individuals in all our intricacies and peculiarities?” He makes the analogy of going into a faux-Korean, Taiwanese restaurant. The food was of sub-par quality and characteristically “un-Korean.” He goes on to contextualize what implications this had both for food and for films, saying, “My film work is my own creation; it is inseparable from my life experience. Everything for me is a source of inspiration, from an old song that I hear, to the coffee shop that I own. Nothing is random, and nothing should be made just for profit.” He argues that the cinema should reflect the qualities of the culture from which it emerged, inseparable from its history and the “flavors” that it was once meant to reflect. The cinema, like this crappy Korean restaurant imposter, has continued to create “products” for economic gain rather than strive for the masterpieces that were once possible.

— Ryan McDonald

The web has globalized the world of cinephilia. Dargis refers to this when she says, “The biggest difference between the cinephilia Sontag eulogized and today’s is that the homogeneity of the marketplace – and the media’s complicity – forces cinephiles to become their own cultural gatekeepers.” By becoming one’s own “cultural gatekeeper,” the modern film enthusiast can gain access to and have even more control over what he or she chooses to watch than ever before. It really is remarkable how many opportunities there are for film enthusiasts to explore and discover new and obscure works, in ways that simply were not possible in the days that Sontag misses so much.

— Austin Kovacs

David Bordwell further shortens the list of “true” cinephiles by separating existing film buffs into two categories depending on their enthusiasm and ritual of movie watching; the cinephile and the cinemaniac. The cinephile, to Bordwell, is more of a connoisseur who appreciates film as art in all its forms while the cinemaniac is more akin to one who consistently watches the same type of movie with established expectations. This distinction creates conflicts between the two authors in regards to what defines a cinephile, but they do agree on one thing: the number of true film lovers is on a steep decline. … Both Bordwell and Sontag would agree that regardless of what distinguishes a cinephile, the true concern is the very real deterioration of movie-going in general. Television and the ability to watch movies at home has eaten into the film culture that used to be so predominant. And now the internet has further decreased the rate at which people go to the movies; with the likes of Netflix, Hulu, and especially BitTorrent, why would one pay ten dollars to sit in a dark room to watch a film with strangers? It is this mindset that has infected the masses and is killing film culture. If it continues Sontag’s fear may become a complete reality – movies may die, only to be resurrected at the birth of a new form of cinephilia.

–Nicholas So

I prefer as close a recreation of the theater experience as possible. Like Rosenbaum, though, I do think what choice you make at the end of the day should hinge simply on what the best format available is. My own personal experience, comparable to his with Vampyr, was with Fellini’s 8½. This is one of my favorite films, and for a very long time I’d experienced only on DVD. I never had a problem with this, but I definitely jumped at the opportunity when I saw that a print was to be screened in San Francisco. That I found myself disappointed with the presentation was saddening, but that I found myself preferring the DVD was surprising! … [What] I witnessed in the theater was a complete degrading of every aspect of the subtitles – vital for correctly connecting with a film like this. Most of the subtitles were clearly outdated, and flowed less or made less sense than my Criterion DVD’s translation. Furthermore, doubly frustrating was the fact that many spoken lines of dialogue didn’t even have translations!

— Leo Robertson (EyeCandy co-editor)

While I understand Sontag’s argument in terms of theater attendance and general audience reception to up-and-coming films, Rosebaum’s article more accurately describes my experience of film, especially regarding the internet’s ability to disseminate independent art. Additionally, Sontag wrote her interpretation of film culture in 1996, which is a year in which my film exposure was probably the sole responsibility of my parents. Today, Netflix plays a role in dictating my film interests alongside the blogs I read and the film courses I take at UCSC.

Written fourteen years later (six years after Sontag’s death), Jonathan Rosenbaum’s introduction to Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition expands on what Sontag theorizes as the potential birth of a new kind of “cine‐love.” He acknowledges that his peers often take the same negative stance as Sontag, but offers a hopeful encapsulation of a younger generation’s experience of taste‐making, suggesting that film culture is merely undergoing [yet another] transition. Rosenbaum, despite being sixty‐six years of age at the release of this publication, admits to viewing films in an “extralegal” manner: downloading them from The Pirate Bay (an ‘underground’ Swedish torrent website).

— Kelsey Carter (EyeCandy co-editor)

In his introduction to Cinephilia & History, or The Wind in the Trees, Christian Keathley touches upon Sontag’s view of cinephilia under attack, viewing it as “something quaint, outmoded, snobbish” in order to ensure films be seen as “unique, unrepeatable, magic experiences” by stating that the goal is “to recover for the present some sense of the excitement… [the] cinephiliac spirit.” To Keathley, cinephilia isn’t something which can be destroyed, for the cinephile beholds certain moments and experiences within films as “nothing less than an epiphany, a revelation. This fetishization of marginal, otherwise ordinary details in the motion picture image is as old as the cinema itself.”

— Travis Wadell

Recently, I watched one of my favorite films again on DVD. I watched it on my laptop, which I’m sure Sontag would not approve of. I also watched the director’s commentary which Rosenbaum would feel is part of the new cinephile experience. I learned some really interesting facts about making the film, but I also learned that the director designed a tight close-up of a character’s face to be viewed on the giant theater screen. He did this so the viewer would feel small and the character would seem appear as omniscient god-like being, because of being so large on screen. While the film still resonates with me and had an emotional impact, I definitely did not get that feeling watching it on my laptop screen. But I also would never have learned about the director’s intent if I hadn’t gotten the DVD and all its bonus features. This example perfectly illustrates the two authors’ points of view on cinephilia and shows that in today’s ever-changing world of movie-watching there is still room for the traditional and the new.

— Lindsey Wachs

Today, I went to the beachfront with my children. I found a sea shell

and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She put the shell to her ear and screamed.

There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never

wants to go back! LoL I know this is completely off topic but I had to tell someone!